by Marisol Marquez

Marisol Marquez (pictured above holding megaphone) is a Chicana member of Freedom Road Socialist Organization and lives in Los Angeles. This essay was originally published in 2020 on Fight Back! News. FRSO is re-posting it now to mark it’s publication as an FRSO print-ready booklet (click here to download).

Los Angeles, CA – September 16, 2019 marked the 50-year anniversary of Chicano Liberation Day. The day was proposed September 16, 1969 in El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, as the date when Chicanos would have Independence. After 50 years we still have not gained our right to self-determination.

My own realization

I was raised in the states of Washington and Georgia but born in Florida. I was not a military brat; I am the daughter of Mexican migrant farm workers. My mother is from Durango, and my father from Hidalgo. Like many who cross the border, their journeys were terrifying and dangerous. My mother, without knowing how to swim, crossed the border by swimming El Rio Grande, and my father hid under a train. Years later my parents were fortunate to become legalized through the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986.

Confused and unsure of how to identify but also unaware of historical oppression of Chicanos, I was a teen when I first identified myself as “Hispanic.” During a conversation with my older brother Raúl, I casually dropped the “I’m a Hispanic” self-identity and accidentally upset my brother. This was around the year 2000 and we were living in the state of Georgia. Raúl firmly said, “You are not Hispanic, you are Chicana.” Somewhere, a Chicana must have raised her fist in the air as he said that.

I’d heard the word before, as our parents jokingly called us Chicanos or Pochos whenever we did something that wasn’t “Mexican.” But I didn’t know Raúl was using the term to describe himself. Raúl and I had not talked about national identity before that afternoon. My brother was born in México, and I knew he wasn’t a U.S. Citizen like I was, but here he was proudly educating me on our Chicanismo. Raúl was already a member of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA) so he asked me to join him during lunch period the very next day, for my first-ever MEChA meeting.

Looking back, I have come to appreciate that being so far from Aztlán, I was fortunate to have gone to a high school that even had a MEChA chapter. Or to have someone else suggest MEChA to me. Our advisor was a proud Chicana who was from Texas. We would become so close to her that she would become our godmother.

Raised as farm workers in a Black Belt South state was difficult for my four siblings and me. We had moved from Washington State and immediately understood we were now a minority in the population – we had lived in the Yakima Valley in Washington, which has a high population of Chicanos as well as American Indians. We became victims of hate crimes, saw dire living conditions, and we connected the most with our Black, Chicano and Mexican field coworkers. Circumstances led my Chicano brother Raúl to land in MEChA, and it paved the way for his younger sisters.

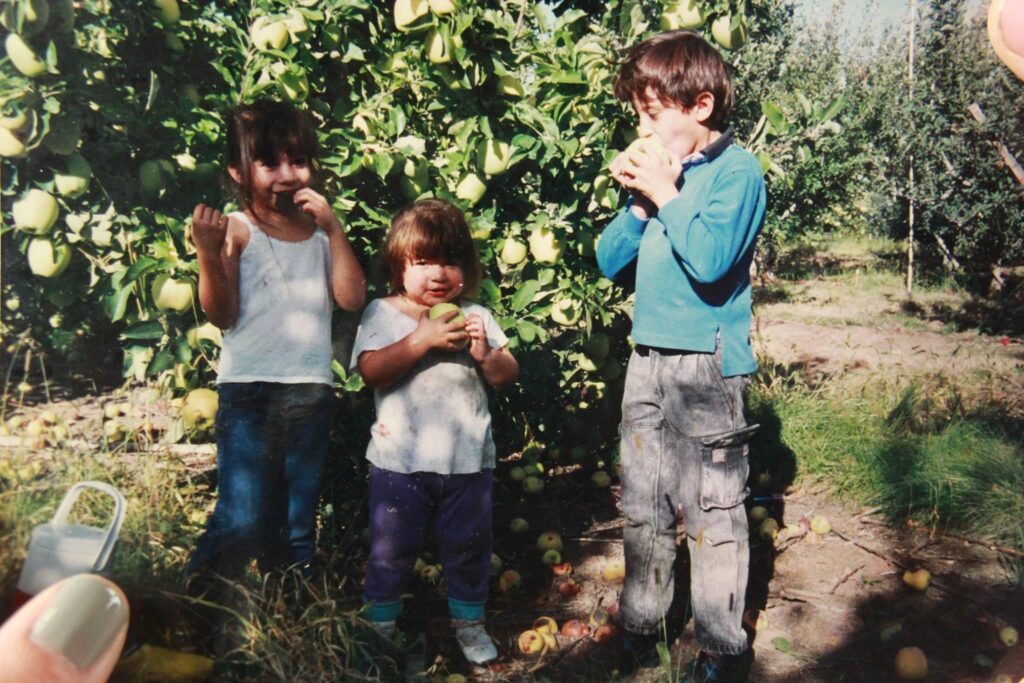

Marisol Márquez, her sister Rosie, and brother Raúl in Washington State.

Finding socialism

Flash forward to 2010 when I moved from Washington State back to the East Coast. I began dating a Florida man (whom I am now married to) who was involved with Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and was also a member of Freedom Road Socialist Organization (FRSO). I was not a member of either organization – as I wasn’t a student and I respected that my partner was busy with his own interests.

It wasn’t until a mutual friend invited me to an SDS meeting that I realized SDS was heavily involved against U.S. wars and occupations. My brother had just left the U.S. Navy and one of my sisters was thinking of joining the military. I was very much against the U.S. invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan, and against my siblings joining the military. So, without thinking twice, I gladly accepted the invitation and attended my first SDS meeting.

Loving SDS but still not a student and still not a communist, it wasn’t until September 24, 2010 that I finally started connecting the dots. That day, anti-war activists, some of them FRSO members, were simultaneously raided on a national level by the FBI. Scared but mostly angry, I also learned the U.S. was investing big amounts of money, time and surveillance on those who opposed U.S. wars and occupations. In particular, the FBI was interested in members of FRSO. I started helping organize solidarity protests against the FBI raids and so it wasn’t long after, that I decided FRSO was the right choice for me.

FRSO – A socialist organization that recognizes the Chicano Nation

We have been fighting for our self-determination because we have to. When we rise, so does the state. When we fight back, so does the state. I am a Marxist-Leninist Chicana and, in my quest, to embrace and push for Chicano self-determination, I joined FRSO. FRSO is the only socialist organization in the U.S. where I can keep being unapologetically Chicana, and that supports the self-determination of the Chicano Nation of Aztlán.

In the 2007 main document Immediate Demands for U.S. Colonies, Indigenous Peoples, and Oppressed Nationalities FRSO states, “In 1836 American settlers in Texas revolted against Mexico and nine years later, the United States annexed Texas. In 1848 the United States attacked Mexico and seized what is now the states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah. In this area of the southwest (including Texas), the United States seized the land of the Mexicans, banned them from independent mining, segregated their children in schools, and suppressed their language, forcing them and millions of immigrants from Mexico to work as laborers in the mines, fields, and factories of the Southwest. These peoples were forged into a Chicano (Mexican-American) nation with a common territory, culture, and economy who have the right to self-determination.”

Chicanos and the National Question

As Marxist-Leninists we believe in what historically constitutes a nation. Aztlán has these characteristics: a common land, common language, a common culture and a common economy. In fact, we have even created our own flags. Presently many of us value and proudly use the flag created by La Raza Unida Party.

Aztlán flag created by La Raza Unida Party.

Chicano’s common history and land

As the FRSO document states, in the defeat of México in the Mexican American war, the U.S. cornered México into signing the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. This happened on February 2, 1848. The treaty made it so that nine current states – California, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, as well as parts of Texas, Wyoming and Kansas – would become part of the U.S.

By 1821, a large portion of Texas (then México) had been illegally overtaken by white settlers. In 1830 México abolished slavery and Texas, riddled with white settlers and their slaves, became extremely angry. They had been extracting minerals, using the land for cattle, and had everything to lose with this change of law. So, with the help of the U.S. government, these white settlers waged a battle with México and won independence in 1836. Another illegal settlement was that of Brigham Young and his Mormon followers, who settled in Utah in 1847.

After 1848 all pleasantries flew out the window – brutal overtaking, theft, and erasure at the hands of the U.S. would become common practice. This subjugation included killing and enslaving the already existing inhabitants of those states – the American Indians and Mexicans. And after the new border, the Mexican people who shared this land with the American Indians would also be trapped. A distinct people, both Mexicans and various American Indian tribes, would once again have a common enemy – only this time it would not be México, France, or Spain; the enemy would be the U.S.

The California Gold Rush that began on January 24, 1848 brought a migration of Mexican workers who knew how to mine the lands. A secondary wave of Mexicans came during the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Congress passed the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act in 1936. Under this act landowners had to share the allocated government subsidies with laborers – mostly Mexicans who worked on their farms. The 1940s would see Bracero programs; forcing Mexicans for-hire to settle throughout the Southwest – now Aztlán. These programs would help start a large and continuous migration of Mexicans into the Southwest, that still exists today.

The naming of the Chicano Nation – Aztlán – happened on March 23, 1969 at the National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference (CYLC) in Denver, Colorado. It was hosted by the Chicano working-class group Crusade for Justice and its important leader Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales. The CYLC which was attended by over 1500 Chicanos, should be remembered as ground-breaking. During the CYLC came the introduction of the first ever Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, written by Mexican-born, Chicano poet Alberto Baltazar Urista Heredia or “Alurista.” Aztlán the word comes from the Aztec Empire and was the Aztec, legendary homeland.

El Plan declared us, the Chicano people, as a Raza cosmica (a Cosmic People) and became the first official naming of our Southwest Nation of Aztlán. El Plan spread like wildfire after the college organization United Mexican American Students (UMAS) named themselves El Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán or MEChA. The name was born in 1969, but not the Chicano nation – the nation had been developing for almost 100 years.

Land has become scarce in Aztlán cities like Los Angeles. Violent gentrification like the one that occurred in Boyle Heights in 2016, has caused Chicanos to make difficult decisions. Many of us are finding ourselves unable to afford homes, land, or rentals. Leaving the city, they were born and raised in, Chicanos are moving to cheaper Aztlán states – Arizona and Texas being the two biggest relocation states.

In current U.S. Census maps, the colors darken and correspond with high concentrations of Chicanos in the states taken from México. Some Chicanos never immigrated; our families lived in the Southwest since before the U.S. conquest. And even more of us are newer Chicanos, like me.

A common language and culture

Chicano pachucos in L.A.

We speak English, Spanish, and our own language, Caló – a mixture of Spanish from all regions of México, Central America, English, and plenty of made-up jargon. Our culture is our own, as we constantly nod to the 1940s Pachuco-era and embrace our Mexican and Central American roots. A basic and perfect understanding of our culture can be found in the book, play or movie Zoot Suit, written by Luis Valdez.

Our favorite music compliments our fight for liberation. Selena exploded on the scene in the 1980s and 90s, forever shaping Tejano/Chicano music as well as Latino music. Despite being murdered in 1995 at the age of 23, Selena continues to break records and inspire numerous people around the world. Recent Chicano musicians like Cuco, Chicano Batman, La Santa Cecilia, Las Cafeteras, and Los Retros have all embraced their Chicanismo. Many of them cite one of the best-known Chicana musicians of all time, Selena, as their inspiration.

Chicano musicians have created entirely new genres of music. Musicians like Cuco and Los Retros created Wavy Soul, and musicians like Herencia de Patrones created Hood Corridos. Their songs commonly include heartache, humor, stories from the streets, and an understanding of being Chicano.

Some people have criticized the original Chicano Movement as not fixing their sexist, homophobic and male-dominated errors. U.S. society teaches everyone to be the absolute worst; billionaire Trump as president further personifies this ideology. We should always challenge backwards thinking, and the current Chicano Movement has been embracing that exact mission.

Since moving to Los Angeles, I have had the pleasure of working and organizing with original Chicana leaders as well as Millennial and Generation Z women. It’s obvious that we also lead. Women throughout history have been the backbone of any working-class struggle, and that statement is also true today.

A common economy

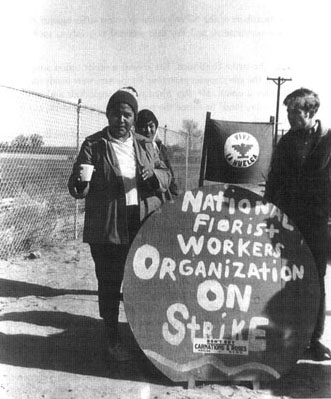

For those reading about Chicanos and Aztlán for the first time, understand that our fight has been rooted in the working class. Chicana Communists like Emma Tenayuca in the 1930s helped organize and lead strikes in Texas pecan-shelling plants. In the 50s, California Chicanas like Soledad “Chole” Alatorre began organizing garment workers. Chicanas during the Empire Zinc Strike in the 50s also participated in the picket lines and helped organize many actions. Chicana Lupe Briseño in Colorado organized the Kitayama Carnation plant in the 60s. So, by the time the 1970s Farah pant strike in San Antonio occurred, revolutionary Chicanas were leading the movement.

Briseño during strike.

Farah strike button

In 1983, the Phelps Dodge Corporation became the setting for a most pivotal series of mine strikes. Phelps Dodge came to Arizona in 1880. Not only was the corporation part of the exploitation process, they were depleting Aztlán’s precious metals in bulk. During the strike, Chicanos were met with the strong-arm of corporations – the U.S. National Guard.

The Chicano economy included cattle, land seizure and sales, mining, oil, farming, and various factory industries. Today Aztlán industries are fewer, as the U.S. has moved factory work to other countries or settled them in Mexican border states. Port work is constant, but oil has diminished. Farming cattle and crops remains a large portion of our economy, as well as land and home sales.

Jobs for Chicanos differ over a large spectrum of professional, semi-professional, self-employment (street vending), trades, and ‘unskilled’ work. I have worked in various kitchens for Los Angeles Unified School District, and most of my coworkers have been Chicanos, Blacks, and Central American, as well as Mexican immigrants.

Retail, hospitality, public sector, and private sector like UPS and port-work are major hubs currently employing Chicanos. The arts are filled with our contributions, too. Gilbert Trejo for example, who is the son of Chicano icon Danny Trejo, has exploded in the music industry and the movie industry. Hollywood alone employs countless Chicanos for creating multi-million-dollar earning movie hits. We are severely underpaid, uninsured and homeless, and creating massive profit for the rich.

Due to the U.S. purposefully denying the existence of a Chicano Nation, numbers and reports on the wealth Chicanos create is hard to find. It is, however, safe to say that we contribute to one of the ten wealthiest states in the U.S. – California.

Indígenismo / the indigenous question

Fighting for Chicano self-determination does not attack or ignore the American Indians’ own fight for sovereignty. They have a right to stand up and fight back, just like we do.

Ernesto Vigil and Corky Gonzalez at Wounded Knee.

We’ve historically united in each other’s fights and our coalitions have existed for half a century. Some of these coalitions consist of American Indians marching with us during the Chicano Moratoriums, and the solidarity demonstrated by Chicanos in the occupation of Alcatraz staged by AIM November 20, 1969.

Another significant battle for American Indians included Wounded Knee in February 27, 1973. AIM occupied Wounded Knee, South Dakota in the name of liberation and against Nixon’s bigoted attacks. Chicanos from all over Aztlán supported the occupation. In 2017 the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) included support from many Chicanos. And most recently, American Indians and Chicanos share a common fight against Trump’s border wall and against border militarization.

The sentiment goes beyond American Indians, we also unite with our Central American counterparts, our Filipino hermanos, Puerto Ricans, Hawaiians, Blacks, Caribeños, South Americans, Alaskan, and countless Asian primos. After all our common enemy is U.S. imperialism which uses the world as a training ground, in learning how to oppress us all at home.

The historical oppression of Chicanos

The U.S. has had time to practice and perfect our oppression. Looking the other way at vigilantes like those who staged the California Bear Flag Revolt in 1846 or the Texas Rangers who ran truly wild, in what they would later dub the land of the “Wild West.”

On January 28, 1918 a true nightmare took place right outside of Porvenir, Texas. 15 children and adults were brutally murdered by Texas Rangers, U.S. Calvary soldiers, and rich landowners. They were kidnapped and led to a hill where they were shot to death. Afterwards, the village was burned down. Nothing happened to the murderers, on the contrary, the Texas Rangers and the U.S. soldiers were hailed as heroes for their cowardly actions.

Los Angeles, having the largest Chicano population of any Aztlán city, has witnessed some of the worst repression against Chicanos.

Large-profile cases like the Zoot Suit uprisings of the 1940s, 1942 the Sleepy Lagoon trial, the 1951 Bloody Christmas attack by LAPD on Chicano inmates, the 1968 East LA 13 – targeting the Chicano high school walkout organizers, the 1970 Biltmore Six case when six Chicanos were accused of starting a fire in the hotel where Governor Ronald Regan was speaking, or the struggle to “Free Los Tres” who organized to kick out drug dealers from East LA.. These are only a few of the cases of repression we have faced. Each of these trials were racist and unfair to Chicanos. Los Angeles had never had a single Chicano or Mexicano on the jury during any of these cases, something that the well-known Chicano attorney Oscar “Zeta” Acosta Fierro, known as the “Brown Buffalo” repeatedly shined a light on.

In Denver, The Crusade for Justice had their headquarters destroyed by fire and two of their members shot and killed by Denver Police. In Northern California, Los Siete de la Raza resulted in a major trial and victory. In the 1970s United Mexican-American Students staged an 18-day occupation at the University of Colorado-Boulder to fight for their education. Two mysterious car bombs killed six of these students, the case now known as the Boulder Six. The Six’s killers have never been found, to this day.

A series of major events took place in the 1960s and early 70s. In Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh and the Vietnamese people successfully staved off U.S. imperialism. There was the victory of the Cuban revolution, highlighting the role of hero and revolutionary Che Guevara. Also, the U.S.-backed coup against Chilean President Salvador Allende strongly influenced a generation of Chicano leaders.

In Vietnam, countless Chicano soldiers were dying. On August 29, 1970 a large coalition marched to call for a stop to the killings of Chicanos at home and oversees, a stop to the war in Vietnam, and liberation from all forms of oppression. This action on August 29th became known as the Chicano Moratorium.

While the Chicano moratorium of August 29, 29170 was not the first moratorium, it was the absolute largest. 30,000 Chicanos took to the streets and gathered to celebrate and plan for liberation. Both the Los Angeles Police Department and the East LA Sheriffs turned the gathering into bloodshed. Three of us were killed – Chicano news reporter and news director Ruben Salazar, Lyn Ward, and José (Angel) Diaz. Over 150 of us would be arrested, and in a true demonstration of racism the LA Times would be silent on the historic event and the state’s repulsive actions.

National Oppression of Aztlán comes in many forms, including police terror and border militarization. In November 2018 Trump, reacting to the Central American refugee caravan, deployed the U.S. military to further exercise militarization and control. Currently the U.S. frontera (border) is flooded with concentration camps crammed with thousands of refugee children – mostly from Central America.

Vigilantes have always been inspired by the cops’ and bandits’ mission of ‘protecting the border.’ America created the Texas Rangers and now racists are encouraged to shoot us by U.S. President Trump.

A white supremacist from Dallas, wrote a manifesto targeting generations of Mexicans (Chicanos), holding us accountable for the ‘Browning of America.’ He drove six hours to the border city of El Paso, Texas, went to a Walmart, and shot 46 people, killing 22. Odessa, Texas also experienced another mass shooter. The press skirting the nationality of the victims, stamped the crime as random.

The U.S. Border Patrol brags about their 71 traffic checkpoints. 33 of these are permanent traffic checkpoints, which operate within 75 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border. For anyone who has entered these checkpoints, one of which is along Interstate 10, they are awful. No matter what your nationality is, these checkpoints are scary, but they are especially so to the undocumented or those of mixed status. The U.S. Border Patrol, combined with vigilantes, makes Aztlán the most heavily militarized region of the U.S. The violations and torture of people seeking refuge are vast and rarely highlighted by the U.S. and its press.

The strategic alliance

Chicanos have experienced great gains in the past 100 years. And yet we still have so much left to win. If we are to liberate ourselves, then we will strike a considerable blow against U.S. imperialism. If we could free ourselves from white supremacy without eliminating capitalism however, we would sadly find ourselves not completely equal. There would still be the very rich, and the very poor. Only this time our rulers would be our own people.

The logical strategy for the Chicano people is to build our movement for national liberation, unite oppressed nationalities, and the multinational working class of this country. This strategic alliance of the national movements and the multinational working class is at the heart of a united front against our common enemy, monopoly capitalism.

Dialectics and contradictions

In the era of Trump, who began his attacks on Mexicans by calling them rapists and drug-dealers, we are seeing the far right wing bolden their attacks.

After 50 years of carrying the name National Council of La Raza, in 2018 the group removed their association with Chicanismo and changed their name to UnidosUS. In April of 2019 at the University of Southern California, El Centro Chicano debated whether to change their name. Originally named in 1972, El Centro Chicano ditched it and became “La Casa.” At the 2019 National MEChA Conference hosted in Los Angeles, many chapters voted to remove the “Chicano” and “Aztlán” portions of their name and developed a new name – Movimiento Estudiantil Progressive Action or MEPA.

On the other side of the coin, some of our victories have included when Tucson Unified School District in 2017 won a Federal case mandating ethnic/Chicano studies in public schools.

More people are becoming increasingly proud of being Chicano. Movies like Walkout, El Chicano, Cesar Chavez, The Rise and Fall of The Brown Buffalo, and about Joaquin Murrieta address our past. Our struggle for freedom will shape our future. It’s dialectics; those who want to hold us back will fail. That is the fate of all oppressors. The Chicano nation needs liberation and that necessity will push us forward.

Moving forward

In Boyle Heights, the Chicano-led group Centro Community Service Organization (CSO) has been commemorating the Chicano Moratorium for the past four years, and did so again this year. They have united with a large coalition to bring forth the 50th Chicano Commemoration. This 50th anniversary will memorialize the August 29, 1970 Chicano moratorium, and continue what it started. They encourage anyone who values the fight for Chicano self-determination to join the coalition and efforts.

Countless Chicano Resource Centers still exist. If you live in Los Angeles, there is one at the East Los Angeles Public Library, or Chicano/Hispanic Student Affairs & Resource Center in Tucson.

We unite with all oppressed peoples – our Black sisters and brothers in the Black Belt South, Puerto Ricans, Filipinos, American Indians, and countless others, and together we turn to face our common enemy: U.S. Imperialism.

Like the lyrics in Los Alvarado’s song Yo Soy Chicano – Yo soy Chicana, tengo color. Puro Chicano, hermano con honor. Cuando me dicen que revolución, defiendo a mi Raza con mucho valor. “I am Chicana, I have color. Pure Chicana my brother, with honor. And when they tell me, ‘Revolution,’ I valiantly defend my people.”

If you are interested in joining Freedom Road Socialist Organization, please message https://frso.org/join/

For those wanting to learn more about Aztlán and Chicanos, I have compiled a reading list.

Book List:

Chicano Movement for Beginners by Maceo Montoya

Occupied America by Rudy Acuña

The Crusade for Justice by Ernesto Vigil

500 Years of Chicana Women’s History by Elizabeth “Betita” Martinez

Chicano! by F. Arturo Rosales

Roots of Chicano Politics by Juan Gómez-Quiñones

Freedom Road Socialist Organization Pieces:

Immediate Demands for U.S. Colonies, Indigenous Peoples, and Oppressed Nationalities

The Immigrant Rights Movement and the Struggle for Full Equality

Class in the U.S. and Our Strategy for Revolution

Other Marxist-Leninist readings on the Chicano National Question:

Resolution on the National Question by the League of Revolutionary Struggle

Fan the Flames – A Revolutionary Position on the Chicano National Question by August 29th Movement

The Struggle for Chicano Liberation by the League of Revolutionary Struggle

Excerpts

How to Tame a Wild Tongue by Gloria Anzaldúa

About the header image:

In 1978, the Congreso de Artistas Chicanos de Aztlán (CACA), a collective of artists of the Estrada courts murals project (Latorre), created this We Are Not a Minority mural in Boyle Heights. It is pictured on the cover of the pamphlet, and at the header of this page.