by the Labor Commission of Freedom Road Socialist Organization

Download a printable pamphlet PDF version of this page

In 2021 the struggle for community control of the police saw an historic advance with the passage of the Empowering Communities for Public Safety (ECPS) ordinance in Chicago. This victory was the result of the alliance between Black-led organizations and labor unions around their shared demand to control how their communities are policed. Additionally, in 2021, 22 local branches or affiliated organizations from around the country met in Chicago for the second conference of the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression. The main program of the NAARPR conference was the fight for community control of the police.

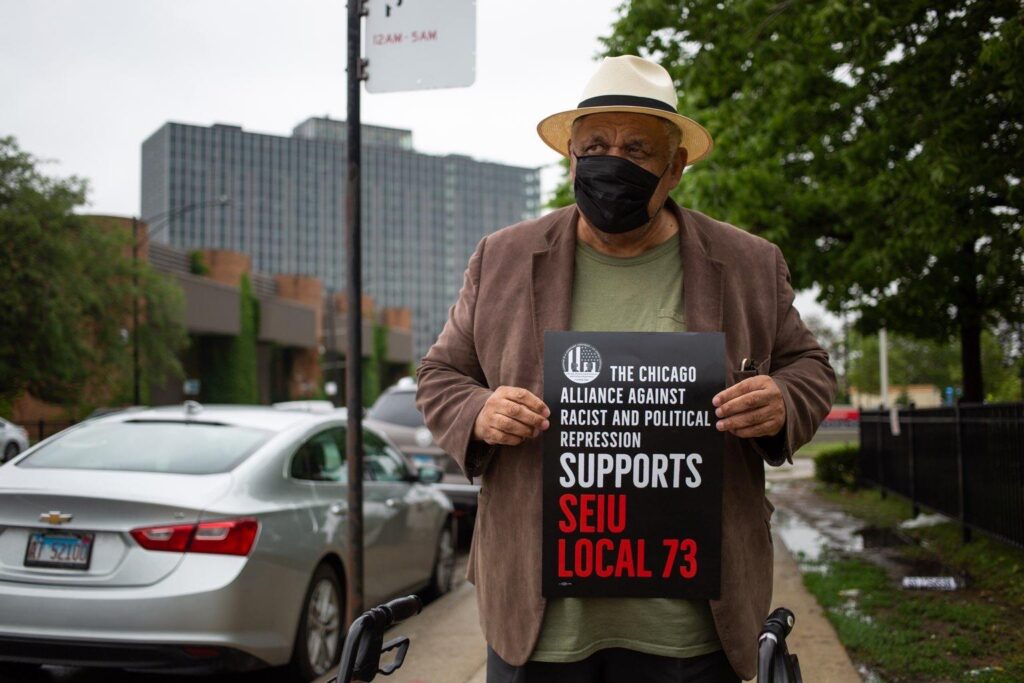

Community control of the police is a longstanding demand of the Black liberation movement, perhaps most associated with the Black Panther Party. With this goal, ECPS was championed by CAARPR (Chicago chapter of NAARPR) and a coalition of scores of organizations, including Black Lives Matter-Chicago, working hand in hand with progressive labor unions such as SEIU Locals HCII and 73, the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU), and more than a dozen more.

The coalition that fought for and secured this victory is an example of FRSO’s call to form and strengthen a strategic alliance between the national liberation movements – especially the Black liberation movement – and the multi-national working class. FRSO sees this strategic alliance as the core of a united front against monopoly capitalism which is essential to a strategy for socialist revolution.

The struggle for community control of the police is rapidly growing – demonstrated by the victory of the passage of ECPS, the second conference of the NAARPR, and the advances in campaigns for community control of the police in a number of cities (Minneapolis, Jacksonville, Dallas, Los Angeles and others).

Brief History of ECPS

On July 21st, 2021, the Chicago City Council passed, and Mayor Lori Lightfoot signed into law, the ECPS ordinance. The legislation had the support of the Black lives matter movement, but passage of the legislation resulted from a final push from the Black-led sections of the labor movement.

CAARPR developed the campaign in 2012 after the murder of a young Black woman, Rekia Boyd, by an off-duty police officer.

The principle behind the legislation drawn up by the CAARPR is community control of the police: that Black and other oppressed people have the democratic right to determine who polices their communities and how they are policed.

The slogan “community control of the police” was first raised by Bobby Seale, chairman of the Black Panther Party. The NAARPR was formed after the successful campaign to Free Angela Davis. Community control of the police was the main campaign they took up.

CAARPR originally called its legislation the Civilian Police Accountability Council (CPAC). They campaigned mainly in Black communities on the South and West Sides of the city. After the Ferguson, Missouri rebellion, activists in SEIU Local 73, a union whose membership in Chicago is 90% Black and Latino, got the local to endorse the legislation in the summer of 2015. Then after the release of the video of the heinous police murder of Laquan McDonald that fall, CTU’s House of Delegates passed a resolution without dissent to support CPAC. The legislation was proposed and fought for by Special Ed teachers, as Laquan was a Special Ed student. Over the next five years, CPAC gained the support of unions with a total membership of 200,000.

The George Floyd rebellion of 2020 brought more labor support, and then early in 2021, a political path to community control revealed itself. Mayor Lightfoot had a watered-down version of CPAC she was supporting, but she betrayed her allies in the city council to keep the power for police accountability in her hands. They came over to negotiate a joint ordinance with CAARPR, which is how ECPS came about.

President Greg Kelley of SEIU Health Care Illinois/Indiana assigned a political staff person from HCII to work full time with CAARPR for ECPS and get it through the city council. HCII staff and member activists phone-banked and held online meetings with their 30,000 members in the city to unite them around community control of the police. Then the members were organized to phone-bank their alderpersons.

The final contribution was when HCII’s Black officers got the president of Local 73, Dian Palmer; and vice president of CTU, Stacy Davis Gates together, then united all the other major Black labor leaders in the city – two Amalgamated Transit Union local presidents, two postal worker local presidents, and the heads of the A. Philip Randolph Institute and Coalition of Black Trade Unionists – to call on the Black Caucus of the city council to come over to support. The Black Caucus was the largest and last caucus to break with Lightfoot and guaranteed a veto-proof majority.

Key methods and tactics, lines and program that made possible the advances in the electoral front in Chicago

1. The support for CPAC, and then ECPS was built through a nine-year campaign of hard organizing mainly on the South and West Sides of Chicago. Without these tens of thousands of hours of mass work, the base for this movement could not have been built. More than 80,000 petition signatures for community control of the police were gathered.

2. Other important methods in the work of CAARPR:

a) In the words of CAARPR Field Organizer and NAARPR Executive Director Frank Chapman, “We must be headlights, not taillights. We must lead people out of their frustration, not into it.” Chapman also calls this, “The duty of conscious intervention.” This means not just uniting with the spontaneous movement but struggling to win it to the program of community control of the police.

b) Of course, uniting with and joining in the spontaneous responses to police crimes; taking a leading role in mobilizations, and eventually becoming the central organizing force within the protest movement. For the Black lives matter movement, this role was recognized when CAARPR organized an August 29, 2015 march of 3000 demanding “CPAC Now!” Their position was cemented with the leading role played in the May 2020 rebellion, bringing 20,000 into the Loop on May 30.

c) Linking the political demand of community control to the “fuel” of the movement – the families of police crimes victims and survivors. The demand for community control of the police has to be linked to the fight against racist mass incarceration.

Key features of line of FRSO and CAARPR

3. Recognition of the national character of the Black liberation movement – the existence of a Black nation within the boundaries of the U.S., with its corresponding classes. Racism comes out of a system of national oppression central to capitalism at its highest stage, in which the ruling class seeks to dominate and exploit entire nations. The Black and Chicano liberation movements long ago struggled to define themselves as nations within a nation.

Among the Black community, there’s a Black capitalist class, or bourgeoisie. Because of racism, most Black capitalists control a tiny amount of capital compared to the white capitalists. There’s also a class of small businesspeople, owning one store, or professionals – doctors and lawyers – which are called the petty bourgeoisie. Then there’s the Black working class. Because they all suffer under racist, national oppression, and can all be victims of racist policing, there can be a united front between them.

These classes exist within the Chicano/Latino and Puerto Rican oppressed nationalities as well.

Without this understanding, we would have missed the opening created when Black alderpersons broke with the mayor. The mayor of Chicago is a Black woman, but she represents the ruling class, not the Black bourgeoisie. This is because of the amount of money needed, and the political support of the Wall Street types and the biggest developers required to get elected mayor in Chicago.

4. The United Front strategy

a) The strategic alliance at the core of the united front.

We oriented to the working-class movement; and we developed an independent base in the multi-national working class, resulting from concentrations of FRSO comrades in SEIU and CTU. From these starting points, and in alliance with the Black liberation movement, we gained support from the most progressive wing of organized labor.

Of course, the vast majority of the mass work of CAARPR was in Black, Chicano/Latino, and Puerto Rican working-class neighborhoods.

Building the Strategic Alliance Through the Labor Movement

(This next section is taken from the FRSO pamphlet, Class Struggle on the Shop Floor: Strategy for a New Generation of Socialists in the United States)

In our efforts to build the strategic alliance from the labor side, we start with the principle that:

“…the working class gains its power through its numbers and its capacity for solidarity, giving it a strategic and material interest in supporting the fight against racism and national oppression.

“We want to bring together anyone and everyone who has conflict with monopoly capitalism to overturn this system. It’s a big tent strategy, although some parts of this big tent are more essential than others. The U.S. has a large multinational working class, but it also has powerful movements of oppressed nationalities, like the Black liberation struggle, which have shaken the ruling class throughout history. Our big tent strategy for revolution in the U.S. must have a strategic alliance between these two movements as its core.

“In concrete terms, socialists in the labor movement need to take up fights against racist discrimination at work and organize coworkers to do the same. While this often takes the form of fighting a racist manager or work policy, it’s no secret that some white workers hold racist and chauvinistic attitudes. But unlike organizing on campus or in the community, labor is the one arena of struggle where the enemy chooses your mass base. We want principled unity among the working class. This doesn’t mean we should coddle backwards views among union members, like so many labor bureaucrats do. It means we commit to long-term struggle, rooted in practice and summation, against white chauvinism.

“Transforming our unions into class struggle organizations opens new possibilities too. Class struggle unions can help in forging this strategic alliance by supporting the fights against national oppression. Take for instance immigrants, especially those from Mexico and Central America, who make up a growing part of the labor movement. The right-wing capitalists who back racist anti-immigrant policies are the same who target the labor movement. We have a common enemy, making it important for the labor movement to take up the struggle for immigrant and refugee rights.”

To add a few additional points: we should promote the leadership of Black and Latino workers within our unions, and make direct connections to Black liberation organizations, like NAARPR, as SEIU and CTU have done in Chicago.

b) The broader united front principles of seeking to unite all forces against monopoly capitalism and national oppression.

CAARPR won support from the Black lives matter movement for community control of the police; then from the other national movements in which close allies already had a leadership role (Chicano/Latino, Arab and Filipino); then social movements starting with the peace, student, LGBTQ and environmental movements.